Distressed Behaviour

Some children with a neurodevelopmental difference may have behaviour that challenges those around them more frequently than other children. This is because they see the world differently and this can be overwhelming. Sometimes distressed behaviour is the only clue we have that something is wrong.

When your child’s behaviour challenges you, it is important to think:

Why did they behave like this? What may have caused it? Sometimes it is easy to see what has triggered the behaviour. It can be simply because someone has said ‘no.’ It may be more complicated e.g. related to sensory issues or the need for a predictable routine. It may be that they have misunderstood but are unable to communicate this easily. Often it may be something in the environment that we have not considered.

Think of this behaviour as an iceberg. When we see an iceberg, we see just the tip of it that is above the water. The largest part is under the water and cannot be seen. The behaviour that we observe is the tip of the iceberg but the many causes for the behaviour are hidden below the surface.

It is important to work out the function of the behaviour. What does the child get from doing it?

For example, “I scream and shout and Mum or Dad takes me out of the shop”. To a bystander, this may look as if the child is spoilt. However, there may be many logical reasons for this behaviour that we have failed to understand. The child may need to escape because the shop is full of adverse sensory experiences: too hot, full of strange smells, too bright or too busy.

Try to monitor and record behaviour over one to two weeks to see if any patterns occur.

Meltdowns and Shutdowns

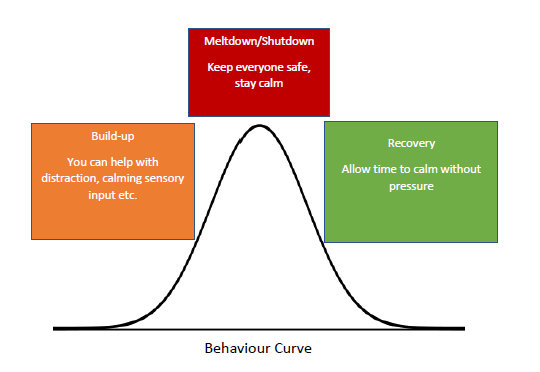

A meltdown or shutdown is an instinctive response to extreme and overwhelming stress which leaves the child incapable of returning to a level of calm at that time. Meltdowns or shutdowns usually occur in three stages: build-up, meltdown/shutdown and recovery.

Build-up phase

This is where the child becomes increasingly anxious. There are often physical or behavioural signs which can be spotted by those who know the child well. This is the best time to intervene, with distraction, limiting instructions, giving calming sensory input or physical activity. Remain calm, and try to make the environment safe.

Meltdown/shutdown phase

This is when behaviour becomes explosive and uncontrolled, or the child may become totally withdrawn and unresponsive. This is a natural biological response where your child has reached maximum stress level causing him to go into instinctive ‘fight or flight’ stress response. The child has little control at this stage as this behaviour is regulated by hormones. It is important to stay calm and make sure that your child and those around are safe.

Recovery phase

This is the stage when the behaviour has passed. The child may be tired and sleepy, may apologise, may deny the behaviour happened at all, or may not remember anything about what happened. Everyone involved is likely to feel emotionally drained. Do not discuss the incident during recovery, wait until you are both rested and calm.

After the recovery stage, find an opportunity to talk about why it happened, and how to support difficult situations to help avoid meltdowns in the future.

Here are some ways to support your child:

Be positive and praise good behaviour. Make sure the praise is given quickly and clearly so that your child knows what you are praising them for. However, also be aware that some children dislike praise as it draws attention to them and the emotion maybe overwhelming.

Don’t try to change too much too soon. Tackle only one thing at a time. Start with whatever will be easiest to change first.

Consider the way you communicate with your child.

Depending on your child’s stage of development, you may be able to help him to understand and change behaviours by explaining about other people’s thoughts and feelings. Social Stories are useful (more advice is available by contacting The Pines).

Use calendars and other visual information to help them understand the concept of time.

Plan ahead for activities and changes to routine.

Watch our Pines Films

Helping Your Child Deal with Change (Parenting Flexibility of Thought)

This film explains why your child may behave in a certain way. By understanding why behaviour happens you will be better able to support the child. Rachael Geddes introduces the theory of things like Executive Functioning in a clear and understandable way, with lots of examples and practical ideas.

Anxiety and Behavioural Challenges in Neurodevelopmental Conditions

A comprehensive film by Rachael Geddes from the Pines team, which looks at anxiety and resulting behaviour. This film will give an understanding of why children with neurodevelopmental differences may behave in particular ways in different situations and what you can do to help. Full of information plus practical strategies and ideas, it looks at the physical impact of anxiety, what impacts anxiety and the ways you can support your child’s behaviour.

Newbold Hope is a small, parent-led organization set up by Yvonne Newbold MBE, to work with families and professional staff from education, health care and social services in reducing anxiety-led difficult and dangerous behaviour in children with an additional need or disability.

Click on image to go to the Newbold Hope website

Updated 21.05.2025